Understanding biodiversity isn’t just about ticking off names. It’s how we recognise what makes a place special. The mix of species in Norfolk’s lagoon tells a story about our reef’s health, its connections to other island systems, and how it may respond to future change. The better we know what’s here, the better we can protect it.

Since returning to live on Norfolk Island in 2018, I’ve spent countless hours snorkelling, filming, and fossicking in our inshore reef lagoon. In the more than five and a half years since I first picked up an underwater camera, I’ve personally recorded 21 species of fish that hadn’t previously been documented within this sheltered stretch of reef. A fellow snorkeller has added a further species to that list to make 22 in total.

How do we know this? Because we have a clear and consistent baseline to compare against – thanks to the lifelong work of Dr Malcolm Francis.

Malcolm is a retired marine scientist and one of the great figures of southern hemisphere fish research. He’s spent almost 40 years working in fisheries science in New Zealand, with a special focus on sharks, rays, and fish distribution across subtropical island groups. He’s also a prolific underwater photographer and author of four editions of Coastal Fishes of New Zealand, a go-to reference for many divers.

Back in 1985, Malcolm began a long-term study documenting the fish fauna of Lord Howe Island, Norfolk Island, and the Kermadecs – all linked by latitude and ocean currents. His 1993 checklist of coastal fishes recorded 235 species for Norfolk Island. It is important to recognise that Malcolm’s list includes fish seen outside the lagoon, in open water, as well as inside the inshore reef area. He’s continued updating that list ever since, thanks in part to sightings contributed by local snorkellers, divers, and scientists alike. You can view his most recent version of the checklist here: Checklist of the coastal fishes of Lord Howe, Norfolk and Kermadec Islands – April 2025 (Figshare)

A banded sergeant – Abudefduf septemfasciatus, first identified in April 2022, hiding in plain sight among a school of blackspot sergeants (top left)

Now, to be clear – not all the 22 newly identified fish inhabiting our lagoons are new. Some may have always been here, quietly doing their thing, just overlooked in earlier surveys. I supect one of these is the banded sergeant, which tends to hang out with the blackspot sergeants, blending in with them (see the photo, right).

Others might be occasional visitors brought here on the currents but then find the conditions unsuitable to support a resident population. For example, it may be too cold and the first winter will send them to meet their maker. Or they could be geographical outliers – like the painted latchet (Pterygotrigla andertoni), which isn’t typically found in shallow coral reef lagoons but rather in deep waters of between 100 and 200 metres in depth. This species is not included in Malcolm’s database for this reason; it was an anomaly.

A few of our new visitors could even be signs of species responding to a changing climate. The sabre squirrelfish (Sargocentron spiniferum), for example, is generally more at home in warmer waters. When it was first spotted here, Malcolm alerted me to the fact that this fish was 750 km south of its previously known range, and may be one of many reef species inching southward as ocean temperatures rise. First recorded here in January 2023, it was recorded here again in December 2024 by Betty Matthews, another snorkeller, and then again by myself in January 2025, so clearly it is persisting here.

Some of these fish are bold and beautiful – like the bluebarred parrotfish – while others, like the black blenny or redstreaked blenny, are tiny, cryptic, and easily missed.

The sabre squirrelfish, found on Norfolk Island, 750 km south of its previously known range

As mentioned above, all but one of these species were first spotted by me while snorkelling in Emily Bay and Slaughter Bay with my camera. The exception is the lattice butterflyfish (Chaetodon rafflesia), a tiny juvenile, which was first seen and photographed by the eagle-eyed Sarah Jenkins.

Whether they’re newcomers or old residents finally getting noticed, these 22 fish add to our understanding of how rich and dynamic Norfolk’s lagoon really is. They also show the power of simple, sustained observation by the general public – with no lab, no funding, and no research vessel needed.

Here is the full list with a photo gallery showcasing each species, below:

Banded sergeant – Abudefduf septemfasciatus April 2022

Black blenny – Enchelyurus ater, February 2023

Blackeye thicklip – Hemigymnus melapterus, April 2024

Black-finned snake eel – Ophichthus altipennis, December 2024

Bluebarred Parrotfish – Scarus ghobban, February 2021

Brokenline wrasse – Stethojulis interrupta, February 2025

Chameleon parrotfish – Scarus chameleon, July 2024

Dot-and-dash Goatfish – Parupeneus barberinus, April 2020

Dusky wrasse – Halichoeres annularis, January 2023

Eclipse butterflyfish – Chaetodon bennetti, April 2024

Fringelip mullet – Moolgarda crenilabis, July 2021

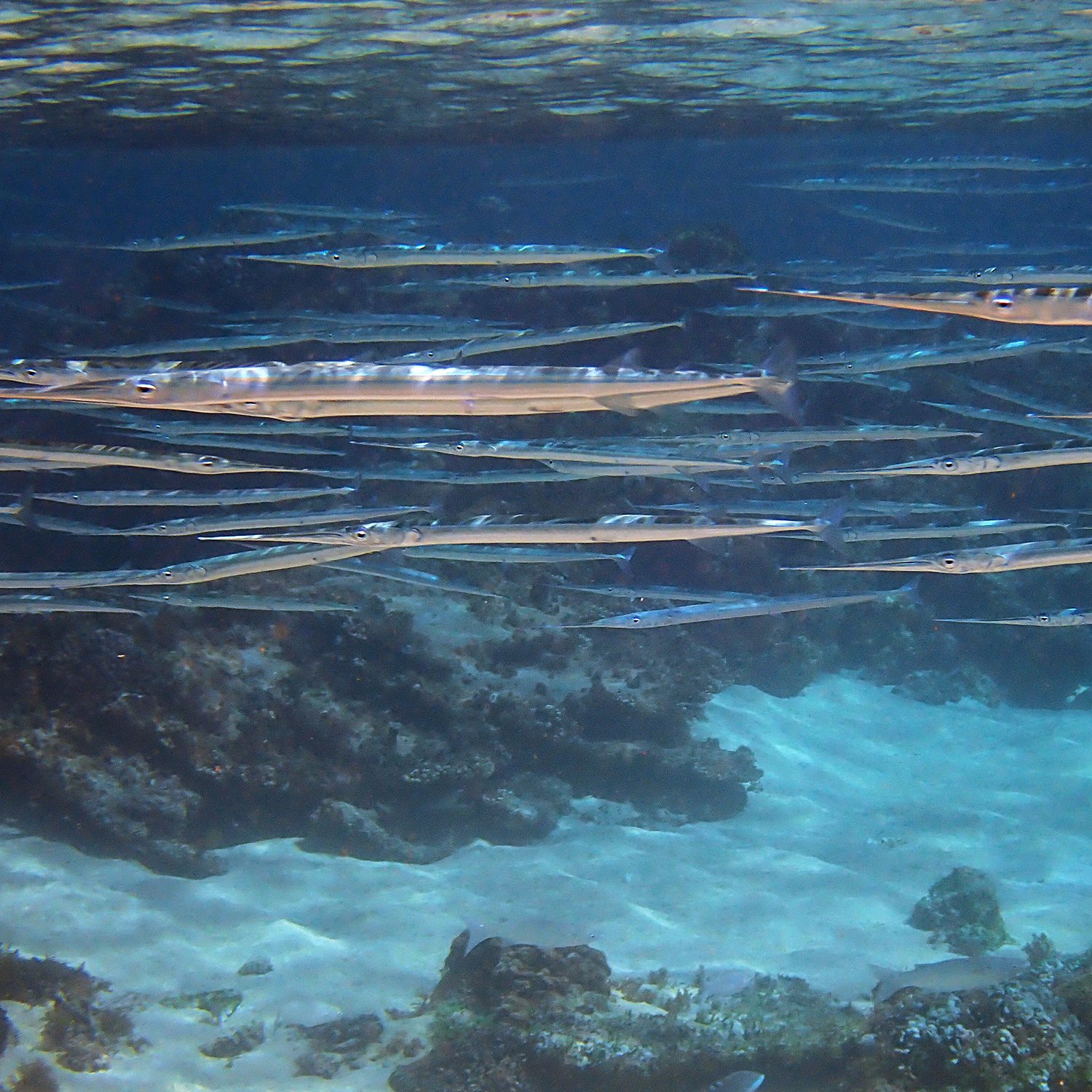

Hornpike Long Tom – Strongylura leiurus, December 2021

Lattice butterflyfish - Chaetodon rafflesia (Sarah), April 2025

Marbled parrotfish – Leptoscarus vaigiensis, January 2021

Pacific double-saddle butterflyfish – Chaetodon ulietensis, April 2023

Painted Latchet – Pterygotrigla andertoni, October 2024

Palenose parrotfish – Scarus Psittacus, May 2021

Redstreaked blenny - Cirripectes stigmaticus, April 2025

Sabre squirrelfish – Sargocentron spiniferum, January 2023

Silverstreak wrasse – Stethojulis strigiventer, June 2020

Twospot demoiselle – Chrysiptera biocellata, December 2024

Yellowbar parrotfish – Scarus schlegeli, August 2024