As the UN Ocean Conference convenes in Nice, France from 9–13 June 2025, global delegates are grappling with the mounting pressures facing the world’s oceans – habitat degradation, pollution, biodiversity loss, and the destabilising impacts of climate change.

On the opposite side of the world, Norfolk Island – a tiny Australian external territory – offers an uncomfortable preview of what is unfolding elsewhere. Our small inshore coral reef lagoon is, in effect, an early warning system: small enough to observe detailed changes, and simple enough to trace many of the drivers of degradation with clarity.

Here, disease outbreaks, growth anomalies (coral ‘cancers’), declining water quality, and nutrient-driven algal blooms are progressively dismantling the reef’s ecological structure – much as they are elsewhere, but on a scale that makes the processes starkly visible. Years of neglect, deferred decisions, and unmanaged land-based runoff have contributed directly to the poor water quality now driving these changes. Norfolk’s reef shows us not only what is happening, but how quickly these shifts can occur when stressors are left unchecked.

This week, alongside the global discussions in Nice, I will post a daily series of photographs and observations documenting these changes as they have unfolded over the past five and a half years. Norfolk Island’s reef may be small, but it is a living case study – a microcosm of what many other coastal ecosystems may soon face unless serious, funded interventions are made.

The warning signs are already here. The question is whether we choose to act.

A healthy flowerpot coral

Tentacles retracted in a flowerpot coral

Day 5 – A century-old brain coral; A daisy-like flowerpot coral

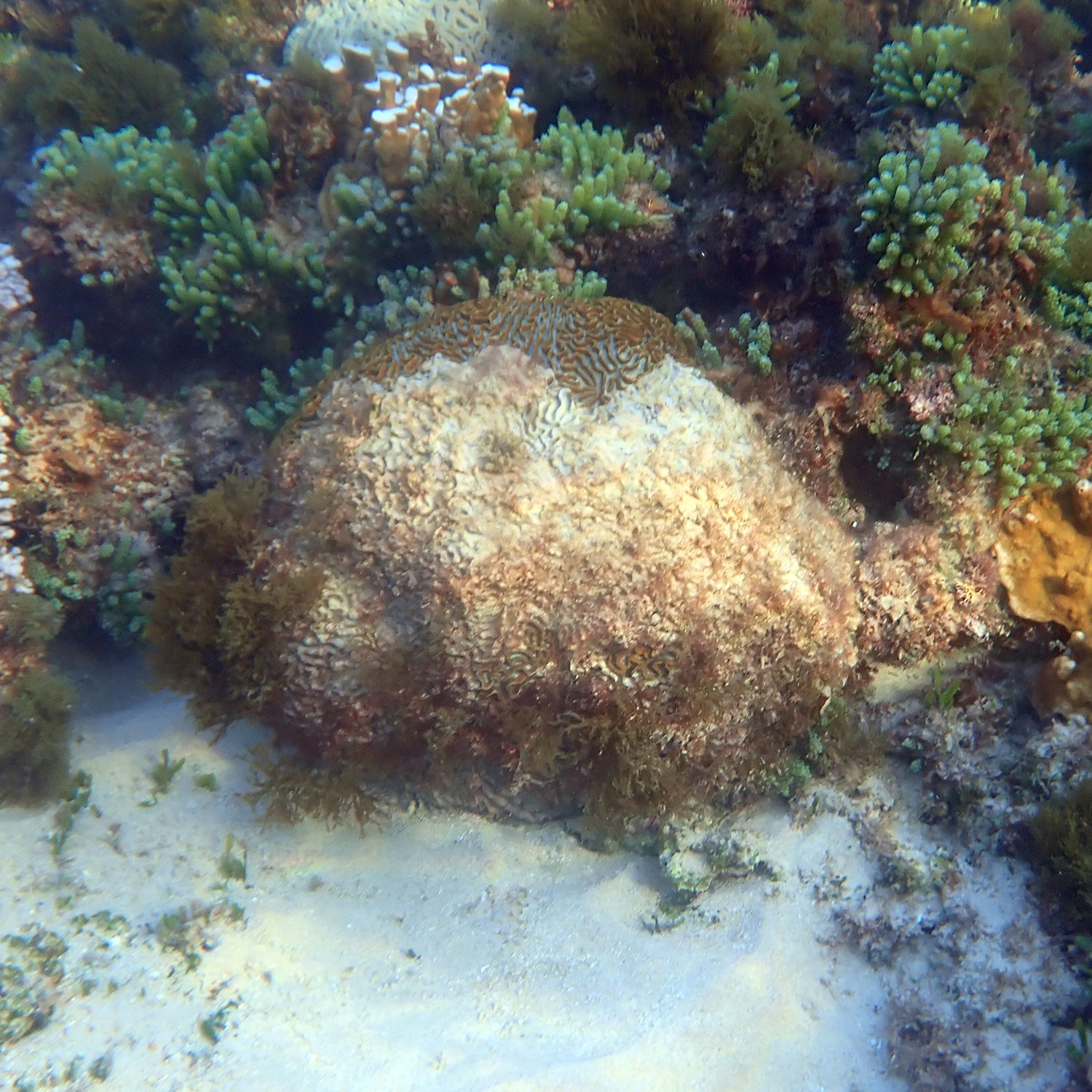

A century-old brain coral. A daisy-like flowerpot coral. Both succumbed to disease in just a few months. Today’s post traces the decline of two slow-growing colonies – and what their fate tells us about the reef’s future.

I have a soft spot for Paragoniastreas – the stony corals often called ‘brain corals’. Each colony wears a unique pattern, like a miniature labyrinth. I could spend hours staring at them. If you search for images of this genus online, chances are you’ll come across some of my photos, thanks to their circulation on iNaturalist.

This is a very slow-growing coral. At Peel Island off Brisbane, scientists have recorded an average growth rate of just 5.6 mm per year. The specimen I’m featuring today is about 600 mm across. Using that estimate – and bearing in mind Norfolk Island’s cooler waters, which likely slow growth further – this coral could easily be more than 100 years old.

But here’s the rub.

In early January 2024, I noticed signs of disease – likely black-band disease – beginning to affect this coral. The tissue loss progressed more slowly than in faster-moving diseases like white syndrome, especially since this is a boulder coral, where infections often move at a more measured pace. But it was just as lethal. By early April, less than 100 days later, most of the colony was dead. Opportunistic algae had already begun to overrun its bare skeleton. When I revisited in May 2025 to get an updated photo for this series, it looked like any other algae-covered boulder with little to show for what had been there 18 months earlier.

That’s a century of growth, lost in a single season.

Coral disease in stony or ‘boulder’ corals isn’t as common here as it is in our more vulnerable Montipora species. But when it does strike, the outcome is still devastating. One by one, we lose colonies – not always dramatically, but steadily and irreversibly.

12 January 2024: the first signs of black-band disease appear on the coral’s lower flank

8 February 2024

29 February 2024

14 March 2024

6 April 2024

14 May 2025: most of the coral is dead, and algae has begun to colonise the skeleton

Just a short swim from this Paragoniastrea colony is another coral I’ve been monitoring – a Goniopora, or flowerpot coral. It’s a a distinctive looking genus of corals with daisy-like polyps. You can see from the close-ups, above, just how beautiful this species really is.

In early 2023, I started photographing this colony too. Sadly, the story follows a similar arc. The first signs of black-band disease appeared mid-year. Over the following months, it crept across the colony, slowly stripping away the living tissue. By March 2024, this Goniopora was little more than a boulder cloaked in algae.

It’s easy to miss the significance of these slow losses – but they add up. These corals took decades to grow. And in the space of a year or two, they’re gone.

These two colonies – one Paragoniastrea, one Goniopora – are just a snapshot. They happen to sit only 20 metres or so apart in a small part of Emily Bay, but what’s happened to them is playing out across the entire lagoon. One by one, coral colonies are succumbing to disease, dying back, and being smothered in algae. Often quietly. Often unnoticed.

This isn’t a one-off incident. It’s a pattern. And unless we improve the conditions these corals are living in – especially water quality – it’s a pattern that will only accelerate.

The two colonies featured today are not far from one of our largest Paragoniastrea colonies – a real giant of the reef (see photo, top). I can’t help but wonder what would happen if this same disease got a foothold there. How long before that coral, too, is reduced to an algal-covered skeleton?

As with the other examples I’ve shared this week, these cases point to a deeper problem. Disease doesn’t emerge in isolation. There’s now strong evidence linking poor water quality – especially elevated nutrients – to coral disease. Norfolk Island’s reef, unfortunately, is no exception. We’ve seen phosphates, nitrates, E. coli, enterococci (indicators of faecal contamination), and even laundry-based whiteners entering the lagoon via groundwater and overland flow.

If we want to give this ecosystem a fighting chance, we need to clean up what’s entering the water.

It really is that simple.

7 May 2023: the disease had already taken hold when I first discovered it

31 May 2023

19 March 2024